Done Quantizing How to Comp and Continue

Some people hate quantization and never use it, while others quantize everything. But there's a middle ground: thinking of quantization as a tool and having enough knowledge to decide when quantization is appropriate — and, just as importantly, when it isn't. Fortunately, quantization is no longer an on-off process. Newer quantization options can be more subtle (and sound far more natural) than traditional, strict quantizing.

But What About the Original Quantization?

The original quantization was musicians playing together and following each other's timing cues. They created the "grid," and that grid's timing ebbed and flowed, often subconsciously — yet in predictable ways. With much music being done solo, it's hard to nail that kind of feel; besides, it's tempting just to turn on a click and play to it. However, what technology takes away, it can sometimes restore — see the inSync article "Nailing the Classic Rock Vibe, Part 1: Tempo" for tips on how you can create tempo variations that form a more "musical" grid to which you can quantize.

Quantization's Evolution

First impressions die hard. Quantization began as a tool in MIDI sequencers that basically put a sledgehammer to your timing and smashed it into a grid. Many musicians saw quantization as a crutch, not a potential creative tool, and dismissed it.

When I first experienced computer-based sequencing (with a Commodore 64!), I was working on an album project with a very talented pianist named Spencer Brewer. After he played into it and saw how much his playing varied from the ideal, he said, "Wow, I guess my timing isn't very good." But after quantizing the part, we realized his timing was actually perfect. The computer could indeed move notes around to fit a formula but was useless for making artistic judgments — the quantized part sounded stiff and unsatisfying.

Fortunately, quantization has changed a lot since those early days and has become much more than just a way to fix sketchy timing. And with most programs, quantization can work with audio as well as with MIDI files.

Correct with Your Ears, Not Your Eyes

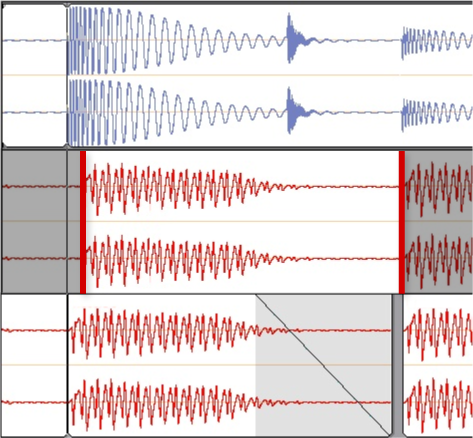

Doctors have it right when they pledge, "First, do no harm." If something doesn't sound wrong, leave it alone (fig. 1).

Figure 1: Track 1 (in Cubase 9.5) is from a drum part played by Nashville drummer Chris Hughes — and it sounds great. Below it is the same section after AudioWarp quantization, which your eyes would say sounds right — but note how the beats outlined in red are just a bit later in the non-quantized version. This gives the part more "feel."

Music is about tension and release. Rushing or lagging the beat a little bit is a natural part of playing music and, in the hands of good musicians, enhances the feel. Quantized and non-quantized parts can even work together as a team — for example, you can complement a rock-solid kick drum with a snare that hits just a little bit late to give a "bigger" sound; or you can push a hi-hat slightly ahead of the beat to give a more rushed, energetic feel. Look at a guitar solo, and you'll often see phrasing that weaves in and out of the beat. If it ain't broke… don't quantize it.

Splitting the Difference

A quantization menu's Strength (also called "Amount") parameter pushes notes closer to the grid, but not on it — think of it as the middle ground between no quantization and snapping everything to the grid (fig. 2). For example, with 50% quantization strength, quantizing a note that's 40ms behind the beat will place it 20ms behind the beat. Quantization strength also lends itself to being used iteratively — for example, use 50% strength and, if that's not enough, try 50% strength again. This is a great way to rein in timing issues and yet avoid an overly quantized sound.

Figure 2: Ableton Live's quantization setup menu is efficient: choose a grid; whether you want to quantize the start, end, or both; and the amount (in this case, it's 90%). You can also quantize to grooves by using the section outlined in red.

Sometimes, Quantization Is Essential

With electronically based dance music, quantization is very common (although, even then there may be non-quantized timing on some elements). When people are dancing, they want a consistent beat. Also, tempo-synched delays and arpeggiators are generally right on the beat, and you don't want parts to clash with these elements. Furthermore, when crossfading between tracks and doing beat-matching, you need consistent timing to avoid train-wreck transitions. Although I'm a proponent of subtle tempo changes (even within dance music — tension and release work there, too), I always make sure the first and last sections of a song have a metronomic tempo to facilitate beat-matching.

The Virtues of Swing

The Swing parameter still quantizes to a grid, but it's a different grid — adding swing lengthens the first note of a pair of equal-value notes and shortens the second note of the pair so that both notes still have the same combined time. Swing is a mainstay with a lot of hip-hop productions; adding a taste of swing to a quantized part can give it a bit more life (fig. 3). You may also find that one instrument using swing doesn't mean everything has to use swing. For example, a drum pattern could have just a hint of swing even if some other instruments use strict quantization. Most of the time, the two won't clash.

Figure 3: DP's Quantize menu consolidates swing (outlined in red) with quantization Sensitivity, Strength, and Randomize parameters.

Make Your Own Grid: Groove Quantization

Although "the grid" implies a rigid rhythmic structure, many programs can follow a groove derived from human timing instead of from a metronome. Groove quantization originally appeared as a MIDI-only feature but often works with audio, too (fig. 4).

Figure 4: In Studio One, the human-played audio drum track has been dragged to the quantize panel's groove window. The arp 1 part is quantized to the drum groove; note how it lines up with the drum track compared to arp 2, the original arpeggiation track. The differences are outlined in red.

For example, suppose you do a recording with a drummer who creates fantastic grooves: extract the drum groove and use it as your grid. Then, you can create a super-tight rhythm section by locking in the bass notes with the drum groove. Groove quantization is also excellent to prevent machine-generated parts (like arpeggiation, as shown in fig. 4) from fighting with parts played by humans.

Again, though, the same cautions apply as standard quantization: you still might need to lead or lag some notes, particularly with solos, to add tension and release to the humanized groove.

Limitations with Quantizing Audio

Quantizing audio can be tricky because it means you need to either lengthen or shorten the audio via time stretching. This can affect the sound quality — the greater the stretch, the greater the likelihood of sonic issues. Some software tries to keep the initial attack intact while stretching the section after the attack. This helps retain a natural sound when quantizing instruments with percussive attacks.

Before going any further, note that manual audio quantization is an alternative — albeit tedious — option. This involves splitting a note just before an attack and moving it forward or backward on the timeline to line up with the grid or with other instruments. If you don't have to stretch the note, then there won't be any loss of fidelity.

When moving a note later in time, the end of the note may slide over the beginning of the next note, but you can trim the first note's decay and add a fadeout to create a smooth transition. Moving the note ahead opens up a gap between it and the next note, which may or may not be a problem (fig. 5).

Figure 5: The top track is a drum part. In the middle track, a bass note lags the kick, so the note has been split (shown by the thick, red vertical lines at the note beginning and end). In the bottom track, the bass note has been moved forward and a decay added for a smooth transition into the gap that was created by moving the note.

If the note being moved doesn't end abruptly at the split, adding a decay (as shown in fig. 5) may be all you need. But if you need to fill in the gap, it may be possible with a sustained note to copy part of the note's end and crossfade it with the end of the note you moved. Otherwise, you'll need to stretch the note end or fade it out.

However, you probably won't want to do manual correction with every note of a part because it's time-consuming. Manual quantization is most useful with single-note solos, where you have a limited number of notes and the line is monophonic. It's easy to isolate the notes and tweak their position just a bit. The irony, though, is that solos are often where playing off the grid is deliberate, so the most satisfying results often come from not quantizing.

Audio Quantization Prep Work

Although most programs let you select a clip or a track and apply mass quantization, listen carefully to what's been quantized. The effectiveness of automatic quantization depends on how well a program's algorithm can detect transients. This is a field where AI may be able to make a substantial contribution in the future, but, meanwhile, it's a challenging task for software designers. Suppose two notes hit in quick succession, with the first quite a bit behind the beat and the second on the beat. If the algorithm doesn't detect the second transient, it may treat both notes as one note. Quantizing will place the first note on the beat but simultaneously drag the second note ahead of the beat.

After listening to the quantized version, you may find that some transients were missed or that transient markers were doubled. This compromises the audio quality. Make note of where the problems are, then undo any mass quantization and split the audio so you can quantize smaller regions. For regions with timing problems, take a look at where the program has placed transients. You may need to remove transient markers or add them. Unfortunately, audio quantization is not always 100% accurate; I've found this kind of manual prep work is often essential when quantizing audio parts.

And just to inject a note of reality: Sometimes it's faster to re-record a part than to try to edit it to perfection. Besides, the re-recorded part may be able to replace sections that don't quantize well — and do so with a lot less hassle than extensive editing.

So… Is Quantization a Crutch?

Others may disagree, but I feel the most important part of creating music is being spontaneous and authentic. This is why it's worth developing playing technique — so that you can play without thinking and have a direct, unfettered connection to what you want to express. But that's also why tools like quantization and pitch correction don't have to suck the life out of music. In fact, they can put life into your music because you can play more freely and spontaneously, knowing that if you play a great part except for a mistake or two, you can fix them.

To circle back to the beginning, the most important aspect of quantization is to use it only if you hear a problem. And if needed, use the flavor of quantization that's most appropriate — maybe it's reduced quantization strength, quantizing to an instrument part, using swing, or quantizing to a strict grid.

Remember, machines don't kill music — people do. Use tools such as quantization artistically, and the results will be artistic.

Source: https://www.sweetwater.com/insync/quantization-when-and-when-not-to-quantize/

0 Response to "Done Quantizing How to Comp and Continue"

Post a Comment